Do You Have Metabolic Syndrome?

How to avoid the health hazard that affects one out of every six Americans.

What is Metabolic Syndrome?

It’s been called Syndrome X, insulin resistance, Reaven’s syndrome, and the “deadly quartet.” But to put it simply, metabolic syndrome is a constellation of conditions that increases your risk of:

- high blood pressure

- high blood glucose

- elevated cholesterol or triglyceride levels

- type 2 diabetes

- premature aging

- the dreaded spare tire around your waist

The World Health Organization considers metabolic syndrome a significant health hazard of the modern world.1

According to the American Heart Association and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, if you have 3 of the following symptoms, you’d be diagnosed with metabolic syndrome:

- Wide waist – for men, 40 inches or larger; for women, 35 inches or larger

- Fasting glucose of 100 mg/dL or higher

- Blood pressure – more than 130 over 85

- Triglycerides – 150 mg/dL or higher

- HDL (good cholesterol) is less than 40 mg for men and less than 50 mg for women.

Consider this a wake-up call. You CAN reverse the symptoms and prevent future health problems by making some lifestyle changes NOW before it’s too late.

Here’s what happens and what you can do to prevent metabolic syndrome and reverse its course.

Over the past several decades, researchers have discovered that insulin levels rise with age, and as they do, the risk of serious disease increases as well. Insulin plays a significant role in aging, chronic illness, middle-age spread, and insulin resistance.

The good news is that weight gain, aging, and illness caused by rising insulin levels are not inevitable. You can stop metabolic syndrome in its tracks, put a brake on your tendency to gain weight (especially where you don't want it!), lose those extra pounds, and slow down the aging process.

How does metabolic syndrome develop?

Metabolic syndrome develops over time mainly from a sedentary lifestyle and a diet high in refined carbohydrates such as bread, starches, sweets, and alcohol. These foods cause blood sugar levels to rise quickly.

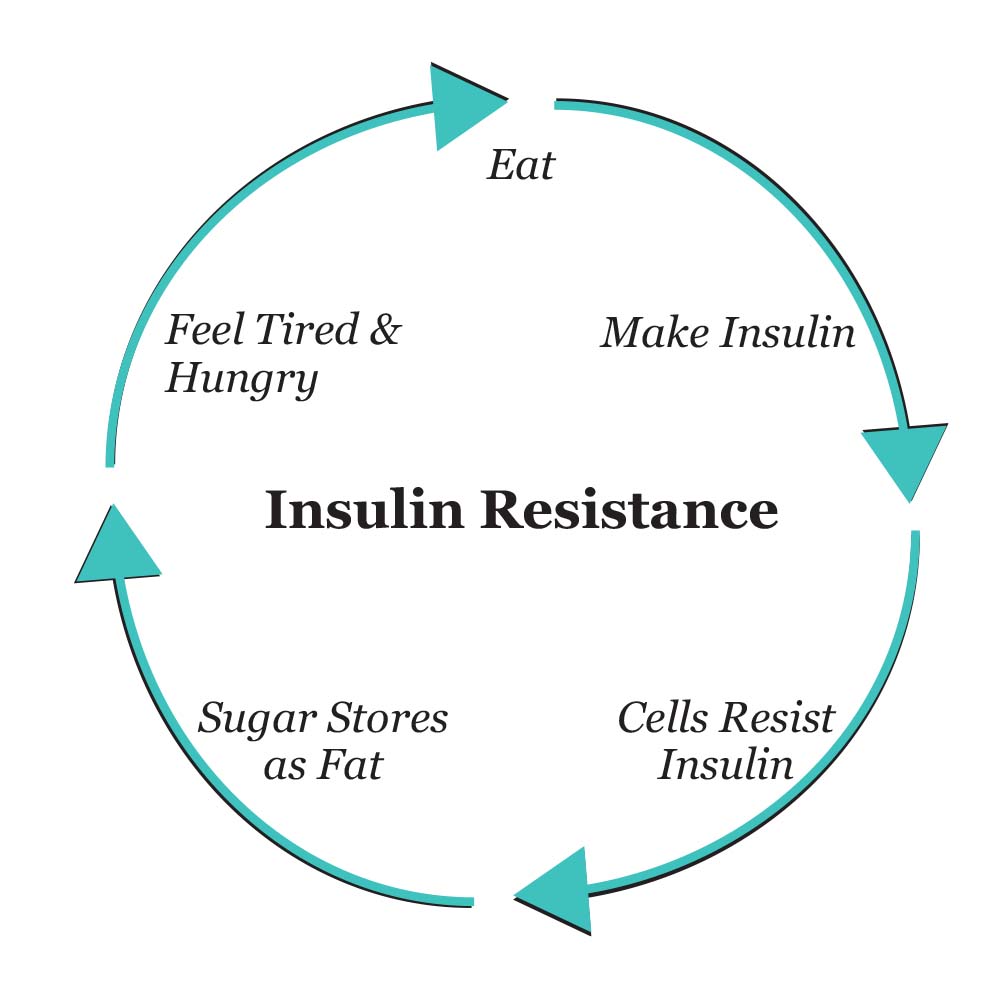

The problem is, the more carbohydrates you eat, the more your body pumps out insulin to deal with the extra blood sugar. If a surplus of insulin continuously floods your body, it becomes sluggish in response to it—and you develop insulin resistance.

Ultimately, this alters blood-fat ratios, raises blood pressure, and increases fat storage, leading to heart disease risk factors known as metabolic syndrome. In addition, high levels of cell-damaging free radicals are also generated, which results in premature aging.

You might not even notice that you have metabolic syndrome because it can act like cicadas that stay underground for years, waiting to emerge by making a racket. Or you might not notice until your waist thickens and you can’t button your favorite pants anymore. Or, even worse, you might not notice until health issues arise and the pancreas can’t keep up with the demand for insulin.

By understanding the mechanism of metabolic syndrome, you’ll be able to avoid it and even reverse it to enjoy more energy and vibrancy, mental clarity, and finally lose the weight around your middle.

Risk Factors for Developing Metabolic Syndrome

- Age – your risk increases with age 2

- Ethnicity – Hispanic community are at the greatest risk 3

- Diabetes – if you had diabetes during pregnancy or if you have a family history of type 2 diabetes 4

- Hormonal imbalances, especially polycystic ovary syndrome 5,6

- Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease 7

- Sedentary lifestyle 8,9

- Smoking 10

- Alcohol consumption 11

- Overweight 12

- Sleep apnea 13-15

- A low-fiber diet with a high glycemic index* 16

- High saturated fat intake 17

- High intake of soft drinks 18

- Frequent consumption of processed meat 17

What happens when you eat carbohydrates?

Carbohydrates are one of the three macronutrients, along with fat and protein. They are the body’s most important energy source, and we can’t live without them. So many of the foods we eat regularly contain some carbs. Yes, even healthy foods like vegetables, grains, nuts, legumes, dairy products, and fruit.

Whenever you eat pasta, rice, crackers, cookies, bread, or even a piece of fruit (which is 50% fructose), the carbohydrates are broken down into individual glucose molecules, are absorbed into your bloodstream. Thanks to the essential hormone called insulin, some glucose will immediately get used by cells that need energy, such as the brain and our muscles. Without adequate insulin, your blood sugar levels rise. When it becomes a chronic condition, it can eventually lead to Type 2 diabetes.

Insulin responds to the rise in blood sugar and is secreted into the bloodstream by the pancreas. This organ is about the size of your hand and lies deep in your abdominal cavity, behind the stomach. In addition to the hormones insulin and glucagon, it makes pancreatic juices containing enzymes released into your digestive system and travel through your blood, breaking down sugars, fats, and starches.

Glycemic index vs. Glycemic load

It’s essential to learn which carbs are good to eat which are not so great because not all carbohydrates act the same. Some are quickly broken down in the intestine, causing the blood sugar level to rise rapidly. As a result, these carbohydrates have a high glycemic index (G.I.).

Glycemic index is a ratio of how high that food raises blood sugar compared to how high table sugar raises blood sugar levels. Foods whose carbohydrates break down slowly release glucose into the bloodstream slowly, so blood sugar levels do not rise high, and therefore, these foods have low glycemic index scores. Those that break down quickly cause a high rise in blood sugar and have a high glycemic index. But a G.I. value tells you only how rapidly a particular carbohydrate turns into sugar. It doesn’t tell you how much of that carbohydrate is in a serving of a specific food.

If you look at tables of glycemic index, you will see things that don’t quite make sense. For example, a carrot has almost the same glycemic index as sugar does. But we all know that carrots are much healthier than table sugar. So to make more sense out of all these, scientists developed a new measure to rank foods called the glycemic load.

Glycemic load (G.L.) tells you how much sugar is in the food, rather than just how high it raises blood sugar levels. To calculate glycemic load, you multiply the grams of carbohydrate in a serving of food by that food’s glycemic index and then divide by 100. For instance, carrots and potatoes both have a high glycemic index, but using the new glycemic load, carrots dropped from a high[jr1] G.I. of 92 to a G.L. of 15, and Potatoes fall from a G.I. of 121 to a G.L. of 20. Air-popped popcorn, with a glycemic index of 55, has a G.L. of 3. 19

But you really don't need to worry about figuring out the glycemic load of the foods you eat. Instead, make it simple for yourself and remember the rule of thumb—Balance your meals, so you always have a good portion of protein (30-40 grams of protein) + piles of low-starch veggies + some fat.

Glycemic Index of Selected Foods*

Food GI Carbohydrates (In a typical portion)

Glucose 100

Potato, baked 98 21

Carrots, cooked 92 16.7 (1 cup)

Honey 92 16 (1 Tbs)

White rice, instant 91 35.8 (1 cup)

Cornflakes 84 21 (1 cup)

Bread, white 74 12 (1 slice)

Bagels 72 38 (1 plain)

Potatoes, mashed 70 24.6 (1 cup/butter & milk)

Bread, wheat 69 11 (1 slice)

Table sugar 65 12 (1 Tbs.), 199 (1 cup)

Beets 64 12 (1cup)

Raisins 61 111 (1 cup)

Oatmeal 61 23 (1 cup)

Bran Muffin 60 19 (1 muffin)

Pita 57 33 (1 pita)

Air-popped popcorn 55 6 (1 cup)

Banana 53 30 (1 banana)

Potato chips 51 10 (10 chips)

Green peas 51 12 (1 cup)

Ice Cream 50 39 (1 cup)

All-bran cereal 44 30 (1 cup)

Whole-grain rye bread 42 12 (1 slice)

Pinto beans 42 49 (1 cup)

Pasta 41 37 (1 cup)

Apple 39 17 (1 apple)

Tomato 38 7 (1 tomato)

Yogurt, plain 38 13 (1 cup)

Chickpeas 36 45 (1 cup)

Skim milk 32 13 (1 cup)

Strawberries 32 11 (1 cup)

Kidney beans 29 42 (1 cup)

Peach 26 10 (1 peach)

Cherries 24 32 (1 cup)

Soybeans 15 22 (1 cup)

Peanuts 13 40 (1 cup, raw)

*Note: Non-starchy vegetables such as leafy greens, sprouts, and broccoli are not listed due to their meager rating. Meat, poultry, fish, eggs, cream, fats, and oils, low carbohydrate foods, are not rated.

To eat a balanced, nutrient-dense diet instead of one that’s carb-heavy, minimize the carbohydrates while maximizing other essential nutrients. If you’re mathematically inclined, you might use this rule of thumb: Minimize your carbohydrate-to-micronutrient ratio. Here are some examples of how this rule is applied:

- Spinach: A vegetable like spinach is great! It has almost no carbohydrates and is rich in vitamins and minerals.

- Blackberries: Even though blackberries have some carbohydrates, the value of vitamins and phytonutrients makes them very worthwhile.

- Sugar: All carb, no micronutrients… you get the idea.

The Role Insulin Plays in Your Body

Insulin and glucagon are the two essential hormones needed for energy storage and utilization. Insulin regulates the metabolism, storage, and level of blood sugar (glucose) as it moves through your body. The pancreas releases insulin when blood glucose levels are high, and it releases glucagon when blood glucose levels are low.

Unused glucose converts to glycogen (a long chain of sugar molecules) stored in the liver and muscles. Glycogen acts as storage fuel like a spare gallon of gasoline for your car and can be converted back into glucose quickly on an as-needed basis. The remaining glucose circulates in the bloodstream to be used for energy. But if more glucose is consumed than can be stored as glycogen, it’s converted to fat for long-term energy storage.

When the pancreas secretes the right amount of insulin, it regulates appetite, growth hormone, cholesterol, fluid levels, and even aspects of your memory and cognition. This is how your metabolic system keeps everything in balance. But when things get out of kilter, a cascade effect occurs, wreaking havoc on the entire system. It might start with your waking up one day, looking in the mirror, and realizing that your waist has expanded an inch or two.

Why am I overweight?

If you’re overweight, you probably crave carbohydrates. It’s not entirely your fault. In part, we crave carbs because we succumb to advertising that makes cookies, chicken nuggets, and cheesy chips look delicious. And they are! Food scientists add substances like salt, artificial flavors, and secret ingredients that get us addicted to unhealthy foods high in salt, fat, sugar, and carbs.

But, your craving is also caused by the way your body overreacts to eating sweets and carbohydrates.

- There’s a strong correlation between high insulin levels and obesity. Elevated insulin levels lead to increased fat cells and larger fat cells.

- High insulin levels will stimulate lipogenesis (fat production and storage) if excess glucose remains in circulation.

- There is evidence that high insulin levels trigger the hypothalamus (the master gland) to send out hunger signals to compound the problem. 20

- Additionally, Leptin, a hormone released from fat cells in adipose tissue, sends signals to your brain when you’ve had enough to eat. Leptin is the satiety hormone because it regulates energy balance by inhibiting hunger. However, overweight individuals have too much Leptin in the blood, which can lead to leptin resistance, a lack of sensitivity to the hormone. When this happens, the individual continues to eat, and the fat cells produce more Leptin to send up a red flag that enough is enough. Although it’s a different hormone, leptin resistance and insulin resistance go hand in hand when dealing with obesity. 21

Insulin regulates carbohydrate metabolism by controlling blood sugar (glucose) levels. Stress and poor eating habits, including overconsumption of carbohydrates, can create an insulin imbalance. During a meal, the insulin level is a determining factor in signaling the brain that your body is “full.” But low insulin levels will elevate glucose and cause you to eat more and gain weight. It becomes a vicious cycle because overweight people burn sugar less effectively than those with a healthy weight.

Kathleen DesMaisons, Ph.D., author of the bestselling book Potatoes Not Prozac, the more carbohydrates you eat, the hungrier you may become.22Even if you restrict your caloric intake, if you are sugar sensitive and eat a diet that’s high in carbohydrates, you may still gain weight.23 Elevated insulin levels lead to increased fat cells and larger fat cells. But please keep in mind that not all carbs are the same. It’s the quality and quantity of carbohydrates that we consume that are important.

According to Australian Dr. Paul Mason, an expert on metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance develops over a long period of time. First, it rises to compensate for the resistance, but there reaches a point where it can’t compensate any longer. Then blood glucose begins to increase, and eventually, your insulin reaches a peak. He calls this “pancreatic burnout.” The sugar which the insulin is trying to control will kill the cells that release the insulin.

The process is reversible if you don’t wait until it’s too late.

Metabolic syndrome is reversible with some lifestyle and dietary changes

5 Things You can do now to Avoid Metabolic Syndrome

- Lose weight. Adopt a healthy eating plan like the Mediterranean, Ketogenic, or Paleo diet. Steer clear of high glycemic food choices like refined grains.

- Commit to shopping the grocery store perimeter, and avoid “junk food” aisles with prepackaged convenience foods. That includes soft drinks, fruit juice, and basically everything white. White rice, bread, pasta, etc., are not your friend. Instead, focus on incorporating more fresh foods and healthy proteins into your diet. Purchase grass-fed, wild-caught, and organic whenever possible. Incorporate small amounts of nuts and seeds for snacks, and avoid high glycemic carbohydrates. Finally, get accustomed to reading labels.

- Divide your plate into three sections: Fill one half with fruits/and or veggies, one-third with a high-quality protein, add a little healthy fat like olive oil, and the remaining portion can be a low G.I options like legumes, grains, or root vegetables. Slow down. Allow the Leptin signal to let you know you’ve eaten enough.

- Get moving! Exercise is the key to staying healthy and reversing the aging process. A morning walk is a great way to grab some zen time and perhaps plot out your day. Or take your BFF along for moral support, especially if this is a new habit you are trying to form. Check out yoga, pilates, dance, or show up to that gym you’ve belonged to forever and remind them you’re still a member 😉. Whichever you choose, make exercising a habit, just like brushing your teeth. Remember, it’s always good to check in with your healthcare practitioner before starting an exercise program.

- Call in the reinforcements! If you need some extra help, take WeBlume’s META-B Berberine to support healthy glucose levels and META-C CARB CONTROL nutritional supplement to block the effects of high glycemic carbohydrates and to slow carbohydrate absorption. Also, include K-LEAN’s C8 MCT oil for rapid energy, mental clarity, hunger suppression, and weight management.

References

- Saklayen MG. The Global Epidemic of the Metabolic Syndrome. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2018 Feb 26;20(2):12. doi: 10.1007/s11906-018-0812-z. PMID: 29480368; PMCID: PMC5866840.

- Mercedes R. Carnethon, Catherine M. Loria, James O. Hill, Stephen Sidney, Peter J. Savage, Kiang Liu. Risk Factors for the Metabolic Syndrome: The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study, 1985–200. Diabetes Care 2004 Nov; 27(11): 2707-2715.https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.27.11.2707

- Campbell B, Aguilar M, Bhuket T, Torres S, Liu B, Wong RJ. Females, Hispanics and older individuals are at greatest risk of developing metabolic syndrome in the U.S. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2016 Oct-Dec;10(4):230-233. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2016.06.014. Epub 2016 Jun 16. PMID: 27342003.

- Vilmi-Kerälä, T., Palomäki, O., Vainio, M. et al. The risk of metabolic syndrome after gestational diabetes mellitus – a hospital-based cohort study. Diabetol Metab Syndr 7, 43 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-015-0038-z

- Ziaei S, Mohseni H. Correlation between Hormonal Statuses and Metabolic Syndrome in Postmenopausal Women. J Family Reprod Health. 2013;7(2):63-66.

- Julie L. Sharpless, Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and the Metabolic Syndrome. Clinical Diabetes 2003 Oct; 21(4): 154-161.https://doi.org/10.2337/diaclin.21.4.154

- Yki-Järvinen H. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease as a cause and a consequence of metabolic syndrome. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014 Nov;2(11):901-10. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70032-4. Epub 2014 Apr 7. PMID: 2473169.

- Zimmet P, Alberti KG, Shaw J. Global and societal implications of the diabetes epidemic. Nature. 2001;414(6865):782–787.

- Hu FB, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ. et al. lifestyle, and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in women. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(11):790–797.

- Manson JE, Ajani UA, Liu S. et al. A prospective study of cigarette smoking and the incidence of diabetes mellitus among U.S. male physicians. Am J Med. 2000;109:538–542.

- Cullmann M, Hilding A, Östenson CG. Alcohol consumption and risk of pre-diabetes and type 2 diabetes development in a Swedish population. Diabet Med. 2012;29(4):441–452.

- Walley AJ, Blakemore AI, Froguel P. Genetics of obesity and the prediction of risk for health. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15(Spec No 2):R124–R130.

- Lindberg E, Theorell-Haglöw J, Svensson M. et al. Sleep apnea and glucose metabolism: a long-term follow-up in a community-based sample. Chest. 2012;142(4):935–942.

- Einhorn D, Stewart DA, Erman MK. et al. Prevalence of sleep apnea in a population of adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Endocr Pract. 2007;13(4):355–362.

- Schober AK, Neurath MF, Harsch IA. Prevalence of sleep apnea in diabetic patients. Clin Respir J. 2011;5(3):165–172.

- Liu S, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Hu FB. et al. A prospective study of whole-grain intake and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in U.S. women. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(9):1409–1415.

- van Dam RM, Willett WC, Rimm EB. et al. Dietary fat and meat intake in relation to risk of 2 diabetes in men. Diabetes care. 2002;25(3):417–424.

- Schulze MB, Manson JE, Ludwig DS. et al. Sugar-sweetened beverages, weight gain, and incidence of type II diabetes in young and middle-aged women. JAMA. 2004;292:927–934.

- Atkinson FS, Foster-Powell K, Brand-Miller JC. International tables of glycemic index and glycemic load values: 2008. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(12):2281-2283. doi:10.2337/dc08-1239

- Ahima RS, Antwi DA. Brain regulation of appetite and satiety. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2008;37(4):811-823. doi:10.1016/j.ecl.2008.08.005

- Kumar R, Mal K, Razaq MK, et al. Association of Leptin With Obesity and Insulin Resistance. Cureus. 2020;12(12):e12178. Published 2020 Dec 19. doi:10.7759/cureus.12178

- DesMaisons, Kathleen, Ph.D. Potatoes Not Prozac, pg. 31, Simon & Schuster, 1998, New York.

- Everson SA, et al. Weight gain and the risk of developing insulin resistance syndrome. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(10):1643-1643.